Laryngopharyngeal Reflux

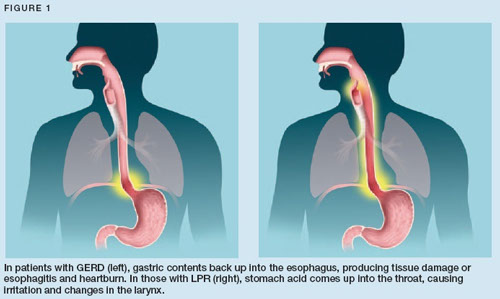

During laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), the contents of the stomach and upper digestive tract may reflux all the way up the esophagus, beyond the upper esophageal sphincter (a ring of muscle at the top of the esophagus), and into the back of the throat and possibly the back of the nasal airway. 80% of patients presenting with this condition do not report heartburn. Symptoms can be varied and sometimes non-specific.

Common symptoms include a sensation of a “lump” or something stuck in throat, frequent throat clearing, difficulty swallowing, hoarseness and a sensation of drainage from the back of the nose (post-nasal drip). Some adults may also experience a burning sensation in the throat. A more uncommon symptom is difficulty breathing, which occurs because the acidic, refluxed material comes in contact with the voice box (larynx) and causes the vocal cords to close to prevent aspiration of the material into the windpipe (trachea). This event is known as “laryngospasm.”

In infants and children, LPR may cause breathing problems such as: cough, hoarseness, stridor (noisy breathing), croup, asthma, sleep-disordered breathing, feeding difficulty (spitting up), turning blue (cyanosis), aspiration, pauses in breathing (apnea), apparent life-threatening event (ALTE), and even a severe deficiency in growth.

Women, men, infants, and children can all have LPR, which may result from physical causes or lifestyle factors. Physical causes can include a malfunctioning or abnormal lower esophageal sphincter muscle (LES), hiatal hernia, abnormal esophageal contractions, and slow emptying of the stomach. Lifestyle factors include diet (chocolate, citrus, fatty foods, spices), destructive habits (overeating, alcohol and tobacco abuse) and even pregnancy. Young children experience GERD and LPR due to the developmental immaturity of both the upper and lower esophageal sphincters. It should also be noted that some patients are just more susceptible to injury from reflux than others. A given amount of refluxed material in one patient may cause very different symptoms in other patients.

LPR can result in significant throat and laryngeal inflammation, and lead to subglottic stenosis (narrowing of the windpipe below the vocal cords) and lesions such as laryngeal ulcers and granulomas. Chronic, untreated reflux into the throat is now considered a small risk factor for laryngeal cancer. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of LPR is hence critical.

Diagnosis & Treatment

LPR is diagnosed by a thorough history of the patient’s symptoms and general health, as well as examination of the throat and voice box using a fiberoptic scope (a very small, lighted flexible tube that is passed through the nose to view the throat and voice box). Traditionally, the diagnosis was also based on the patient’s response to a trial of treatment with acid-suppression medications and reflux precautions through diet and lifestyle changes. However, we now understand that some patients require high-dose therapy (often two to four times the dose routinely recommended for gastro-esophageal reflux disease) for prolonged periods of time. Surgery to control reflux may be recommended in some patients who don’t respond to medications.

New England ENT is one of the few centers in the country to offer a highly sensitive, outpatient diagnostic test (Restech Dx-pH Measurement system) to quantitatively measure the degree of reflux into the throat. This is a simple, comfortable test performed with a small probe containing a senor at the tip. It is passed through the nose until the tip is at the back of the throat (high enough that patients cannot feel it when speaking or swallowing). The probe wirelessly records the acid exposure (every 30 seconds) over a 24-hour period. Patients can eat normal meals, go to work and even exercise during the testing period. With the patient’s input, the Dx-System tracks meals, symptoms and supine periods. This helps correlate symptoms and reflux patterns. This is a valuable tool in the comprehensive assessment of patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux.

Most people with LPR respond favorably to a combination of medications and lifestyle changes. Medications that could be prescribed include proton-pump inhibitors, histamine antagonists, antacids, pro-motility drugs, and foam barrier medications. Some of these medications are now available over the counter and do not require a prescription. Patients who fail medical treatment or have anatomical abnormalities may require surgical intervention. Such treatment includes fundoplication, a procedure where a part of the stomach is wrapped around the lower esophagus to tighten the LES, or endoscopic techniques to make the LES tighter.